African American Genealogy

Why Is African American Genealogy Different?

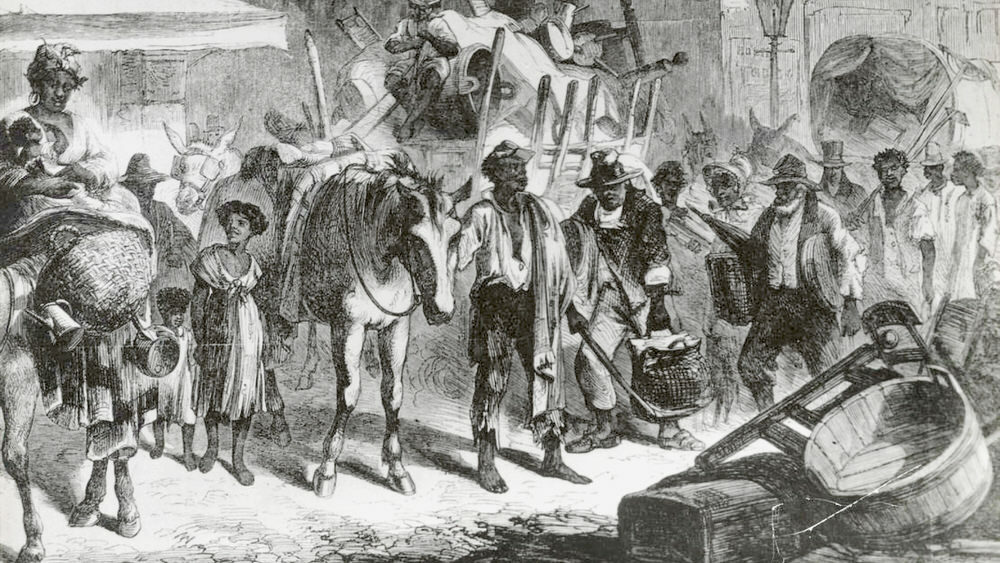

African American genealogical research is different from other ethnic backgrounds. Because slaves were considered property, they were prohibited from reading, writing, attending school, legally marrying, owning land, owning a business, voting, and participating in many other activities that generate records on which much genealogical research is based.

Citizenship was granted in 1868 to slaves, an action that had an impact on records like letters, diaries, wills, census records, land deeds, voter registrations, and school records.

However, like people of that time, written documents were sometimes segregated. These records might be kept in separate files or listed in the back of record books. Finding aids may also have these complications. For example, many military records of African Americans are indexed separately.

Finally, African American genealogy and history has not been widely researched. When Alex Haley wrote his best-selling book Roots, many people began to question their elders about their past and research their own family histories. But this has only occurred in the most recent past. There’s a lot of history to try to catch up with!

Getting Started

Start with yourself and work backwards. Write down where and when you were born. If you’ve been married, list that as well. Make sure you have documents such as your birth and marriage certificates. Most birth certificates list the mother and father, where they were born, and how old they were at the time of the birth. That’s your next step. You can start with your mother’s or your father’s side. Collect all of their documents.

Each state has a vital records office, which will give you copies of documents for a fee. You can continue to research this way until you can no longer locate the documents you need.

Gather Oral Histories & Family Records

Try to write your own autobiography. Start with yourself and work backwards, writing everything you know about your parents, grandparents, and so forth. Interviewing the elders in your family is always helpful. Ask them what they can remember about what life was like when they were younger, and about the ancestors they remember.

Find family papers, records, photos, and souvenirs. Make sure to write on the backs of photos who the people are on the front, when the photo was taken, and if it’s a specific occasion, such as a birthday, graduation, or baptism.

Sources for Researching African American Genealogy

Records and Documents

The following sources have records after 1870:

- Cemeteries

- Funeral homes

- Birth and death certifications

- Marriage and divorce records

- Obituaries

- Published biographies and family histories

- Old city directories and telephone directories

- Social security records

- U.S. census records

- African colonization societies

It’s more difficult to research prior to 1868, but it doesn’t mean there are no records. You will want to try to:

- Identify the last slave owner

- Manumissions and Certificates of Freedom

- Business receipts and contracts

- Research slave owner and slavery history

- Runaway slave advertisements and legal notices

- Bounty lists

- Freedmen’s Bureau: Established in the War Department by an act of March 3, 1865 the Bureau supervised all relief and educational activities relating to refugees and freedmen, including issuing rations, clothing, and medicine.

- Explore Canadian and Caribbean transits

- Slaves were sent to ports other than those in the United States. Many slaves were sent to the Caribbean first and then to the U.S., some even after a generation or more.

Recommended Resources

Internet

- National Archives and Records Administration - Features a guide for genealogy researchers (includes upcoming workshops and events, templates, and research tools), and a guide to records specific to African Americans.

- Maryland State Archives - Features a guide for genealogy researchers, a guide to records specific to African Americans, a database of records and website about slavery in MD, additional images of primary resource records, and Baltimore City Freedom Records.

- Library of Congress - Local History and Genealogy Reference Services - Features guides for genealogy researchers and digitized collections pertaining to U.S. History (e.g. Slavery and Law, Slave Narratives, African American Pamphlets).

- Digital Maryland - Includes collections such as the African American Funeral Programs, Manumissions, Indentures, Bills of Sale , Mapping Maryland's Counties, Slave Documents, and Views of African American Life in MD.

- Maryland Historical Society - Features a guide for genealogy researchers, as well as one specific to resources they offer about African Americans.

- Afrigeneas - Features user submitted resources (slave data collection; photographs; census, death and marriage records), and communal features (mailing lists, option to create an email account, message boards, daily and weekly chat).

- Trans-Atlantic Slave Database - Information on over 35,000 slaving voyages that occurred between 1514 and 1866, manipulable into maps, timelines, tables, and graphs. Includes African Names Database, recommended websites, essays to provide context, and images (manuscripts, places, slaves, and vessels).

- Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, and Delaware - Listing of free African Americans in the Southeast during the colonial period extracted from primary source materials.

Books

- Burroughs, Tony. Black Roots: A Beginner’s Guide to Tracing the African American Family Tree. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. E185.96 .B94 2001

Focuses on preparing the reader to conduct a well-organized search. Includes didactic case studies from a renowned researcher of African American genealogy (the author) and other researchers, and many images of sample genealogical documents with feedback on how to make use of them.

- Smith, Franklin Carter. A Genealogist's Guide to Discovering your African-American Ancestors : how to find and record your unique heritage. Ohio: Betterway Books, 2003. E185.96 .S6514 2003Q

Beginning chapters describe how to conduct prep work and make use of historical governmental records; middle chapters highlight relevant customs (e.g. naming practices) and information available through research of slaveholder families; and ending chapters are didactic case studies.

- Woodtor, Dee. Finding a Place Called Home: A Guide to African-American Genealogy and Historical Identity. New York: Random House, 1999. E185.96 .W69 1999

A highly detailed how-to-manual that provides readers a historical and cultural context. Points out typically overlooked records, how to assess validity of records, and provides case studies, images and diagrams, and related topics (e.g. family reunions, publication of findings, etc.).

Recent Guides

COVID-19 Vaccine Information Dec 21, 2020

COVID-19 Vaccine Information Dec 21, 2020 COVID-19:

Links You Can Trust Jul 23, 2020

COVID-19:

Links You Can Trust Jul 23, 2020